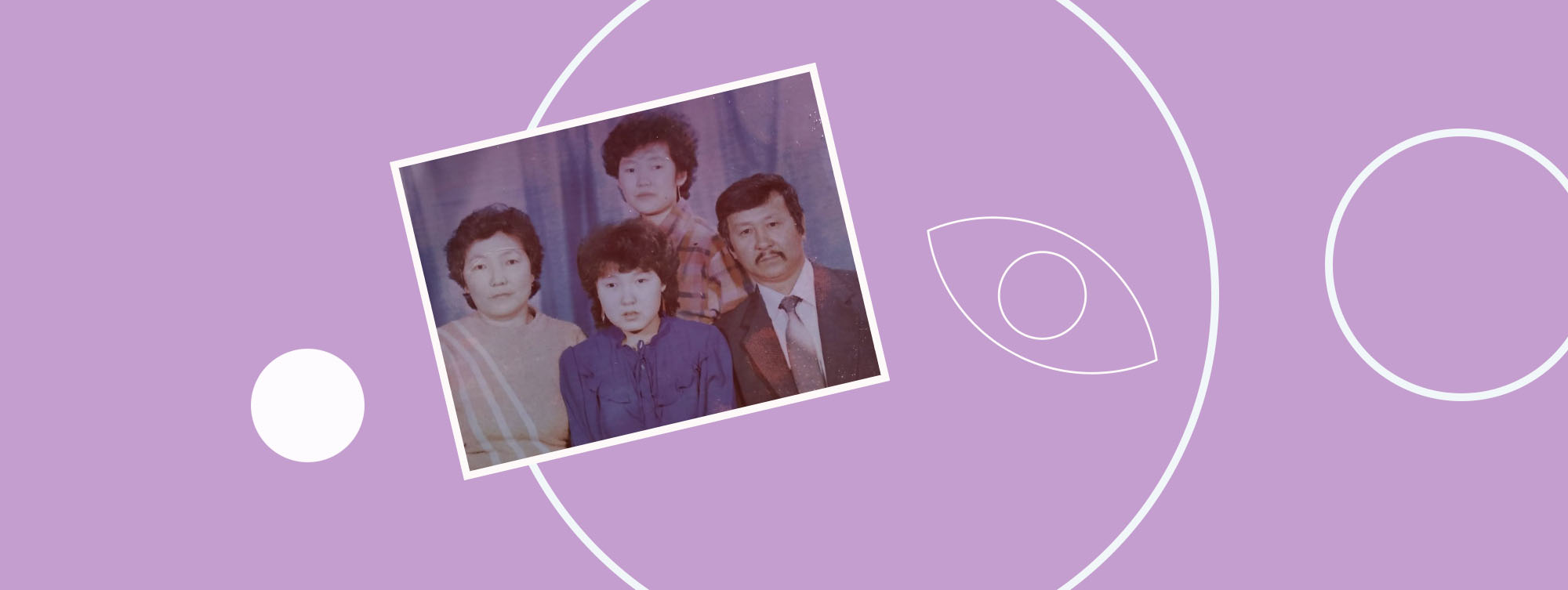

The visual impairments, caused by eye diseases, show themselves very differently. It can be decline in visual acuity, or visual field constriction, or distorted color vision, or photophobia, etc. In her column for “Special View”, Tsyndyma Boyko, the editor of the “All-Russian Society of the Blind Radio”, told how her retinitis pigmentosa affected her sight in her childhood and how she sees today.

My parents were young, when they had me, and they had no visual impairments. When I was 6 months old, my mom noticed that I didn’t react at some toys and that I focused on spots of bright light. She took me to the doctors, and they diagnosed “retinitis pigmentosa”. This is a genetic disorder that happened to me because both my parents were carrying a damaged gene. A patient with such a diagnosis will slowly lose his/her sight, but that moment my parents and I didn’t know it.

In a year and a half my younger sister was born and unfortunately had same disease. Originally, she saw a bit better than me, and it was easier for her to read books, so she read a lot of them until her sight went down. She even read to me out loud.

While we were kids, our sight was quite enough to play, frolic, ride a bicycle, sled down the hill and run with other children outside. But this was all possible only in the daytime. With the poor lighting the sight worsened, as at night only the streetlamps and the lit windows were shining bright on a completely black background.

I still don’t like autumn and winter because of long nights. It was especially hard in the residential school for visually impaired children, since dormitories, school and canteen were all situated in different buildings. We walked outside guided solely by bright spotlights on the buildings. It was especially bad during wintertime, when on your way to the canteen you had to cross an icy path, where other guys usually sled down. That moment you had to rely only on hearing.

Right after quickly stepping from a sunny day into a room, we lost any ability to navigate — our disease makes retina adapt longer to the lightning changes. You had to wait a couple of minutes to get used to it. To make the contrast milder I wore sunglasses and took them off when entering a building. I experienced same difficulties when I had to go to a subway.

My sister had an incident once: she went out into the corridor from a well-lit classroom and passed by a teacher. The teacher made a point on the fact that my sister didn’t say hello to her. My sister confessed she hadn’t noticed her and then the teacher was outraged: “Didn’t notice me, that big?”

Audio description: photo in color. Top view. There are a woman and a girl sitting on a sofa, surrounded by kids’ books. The woman holds an open tactile book, with an application image at the centerfold. It shows an orange star and the Three Kings, walking one after another. Their bright clothes, beards, moustache and hats are made from pieces of cloth and fur. The girl carefully touches the shape in the middle.

A narrow field of view didn’t allow me to read fast. I could read a book only if there was good lightning and clear font. Magnifying glass was useless — well, only for very short texts maybe. Even in special-needs-schools some teachers couldn’t understand the peculiarities of our sight, which caused misunderstandings. For example, I could get an “F” for reading. I was nervous any time I had to read a text paragraph and summarize it afterwards — simply because I couldn’t read it all on time. Fortunately, I wasn’t asked. It was after school already when I realized that the teacher did understand I wasn’t able to read a paragraph fast enough.

Moreover, my sister and I had troubles identifying colors, which is also a typical attribute of retinitis pigmentosa. It was hard for us to define some shades of green and blue, yellow and orange, rose and red. At school I loved drawing and I asked my classmates to help me with colors of pencils. Once they decided to play a joke on me and gave me blue pencil instead of green. They then were laughing at me for quite long afterwards and showing everybody in the school those blue leaves that I painted.

Sometimes PE classes turned out to be a challenge. Apparently, our PE teacher was quite experienced, but he demanded that we performed a vault — and it was terribly difficult for me to find a handhold and jump in the right place. It was equally hard to walk on a log which had same color as the floor, in the poor lightning of the gym. Everything changed to better when a new, competent young teacher arrived. He replaced the vaults with standing long jumps and installed parallel bars, where I felt myself a real monkey. Parallel bars became my favorite spot in the gym.

In the residential school canteen we set our duties ourselves: we laid and cleaned the tables on our own. My field of view was narrow, and if I carried the dishes and focused straight in front of me so not to hurt anyone, I could throw around all the stools I found on my way. If I instead watched my step, I would inevitably run into people. I always had to make this hard choice.

Going down the stairs caused other difficulties, especially when the edges of the stair levels were not marked with a contrasting line. Going upstairs was easier. Kerbs, painted with contrasting colors, also helped to navigate.

My sister and I lost sight slowly, so we managed to finish school with commonly used paper schoolbooks. However, in 9th grade I had only 20% of my sight left, out of my general 30%. That moment I thought for the very first time that one day I would lose the sight completely. This came out during medical examination that I had in the beginning of the school year. Terrified, I approached our school ophthalmologist and asked if this was true and I would become blind. He confirmed, and I was shocked. I cried for several days, but then decided it would not happen too soon and continued my studies.

Reading schoolbooks became even harder, compared to secondary school period. As I mentioned, the sight weakened, while the large-print books for high school didn’t exist. All the classmates helped me, and thanks to that I managed to graduate with above average score. However, that time I had no intention to go on to higher education. I didn’t have enough sight for reading and I didn’t learn Braille system, so I laughed saying I graduated being “illiterate”. While my sister was able to read normal paper books long after graduating from school and went to work on her own.

That time, along with the certificate of secondary education we got qualification of massage therapist and could work in medical institutions. I worked in clinic and then in rehabilitation center for 13 years. Even today I get back to massage and take care about my family’s and friends’ health.

Audio description: photo in color. A masseur is warming up his patient’s wrist. His hand is lying on a light-colored terrycloth blanket. The therapist has strong hands with shortly trimmed nails.

Later I got married, had a daughter and in five years — a son. My sister became a high-class specialist in baby massage, gave birth to two lovely sons. Nevertheless, in that period our sight declined steadily. My sister and I looked for any possible ways to maintain our sight, took medical treatments in hospitals, addressed Tibetan doctors, I even had surgery by Ernst Muldashev, in Ufa. One moment we realized there is too little effect from these manipulations and stopped trying. Fortunately, our children and grandchildren didn’t inherit eyes problems.

With the development of information technologies, I figured out I could read books and get higher education. I was 30, when I entered the university, then got my bachelor’s degree, then master’s degree, then finished Graduate School. Currently I work as a radio editor.

In between the period, when I still could see, and the moment I stopped identifying the objects I had terrible headaches. That was probably because I still had a habit to rely on sight and tried too hard to continue doing it. First the objects’ contours disappeared, but I could still see bright colors, then only silhouettes stayed, then lamps and computer monitors, in the shape of light dots, and currently I can see only bright sunlight.

Today genetic engineering is developing fast, and diseases, such as our, become curable. However, you have to have at least some residual vision. Doctors say, it is possible to restore my sister’s sight, since she has more sight left. In my case it might be too late.

I want to address people with retinitis pigmentosa: take care of your eyesight, lead a healthy lifestyle, take vitamins and preventive treatments. This will give you bigger chance to wait for new healing methods and get your vision back.

Before I loved to look at photographs — I knew I would lose my sight, sooner or later, and I wanted to save all the faces in my memory. Even today I keep seeing them. Now I try to take photos of everything that happens to me and all the people around — and I do believe I will be able to see these photos, one day.

Retinitis pigmentosa is an inherited condition, when retina slowly deteriorates, causing total blindness in the end.